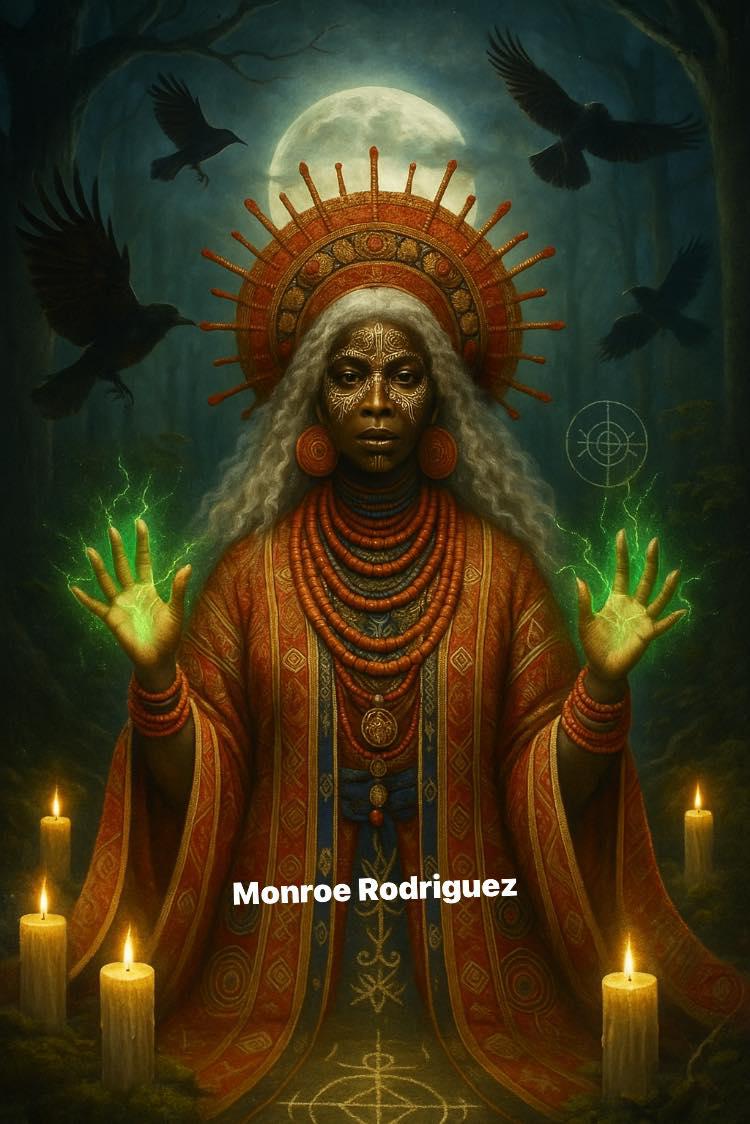

Ìyáàmi Ṣoròngá: Mothers of Mysteries in Yoruba Cosmology

The concept of Ìyáàmi Ṣoròngá occupies a central yet often veiled position within the spiritual and philosophical worldview of the Yoruba people. Frequently translated as “Our Mysterious Mothers” or “Mothers of the Night,” the Ìyáàmi constitute a collective of powerful, primordial feminine forces whose influence permeates both the seen and unseen realms. Their mysteries, though closely guarded within Yoruba society, are essential for understanding the balance of spiritual power, morality, and authority in Yoruba thought.

Etymology and Identity

The term Ìyáàmi derives from “ìyá” (mother) and “àmi” (my or our), while Ṣoròngá is an honorific or mystical title, the meaning of which is purposely ambiguous and protected. Collectively, Ìyáàmi Ṣoròngá refers to an ancient sisterhood of spiritual mothers whose origins predate the Orisa pantheon and whose powers are associated with creation, destruction, protection, and the administration of justice.

Theological Significance

In Yoruba cosmology, the Ìyáàmi are regarded as the custodians of àṣẹ (spiritual power, authority, and manifestation). They are the spiritual mothers of all Orisa, humans, and spirits. Their association with birds—especially owls, vultures, and other nocturnal or mysterious birds—serves as a potent symbol of their connection to the liminal spaces between worlds, the mysteries of the night, and the power to bless or withhold blessings.

While they are often described as “witches” (aje), this term in Yoruba thought does not carry the exclusively negative connotation it has in the West. Instead, it refers to those with deep spiritual potency, particularly in the domains of birth, transformation, and justice. The Ìyáàmi possess the ultimate veto over any ritual or ceremony, including those conducted by the most celebrated priests or kings. In some traditions, they are also seen as guardians of oaths and enforcers of cosmic and social order.

Secrecy, Authority, and Moral Order

The Ìyáàmi are renowned for their secrecy and autonomy. Their inner workings and rituals are not accessible to the general public, nor to most initiated priests. Membership in the Ìyáàmi is not acquired through standard initiation but is said to be inherited through bloodlines or spiritual selection. This separation reinforces their role as guardians of sacred knowledge and the “checks and balances” on political, royal, and spiritual authority.

Within the Yoruba worldview, no king, priest, or Orisa can function in defiance of the Ìyáàmi without consequence. Stories abound in the oral literature of kings and priests seeking the blessings of the Ìyáàmi before major undertakings. Their power is respected, sometimes feared, but always acknowledged as foundational to communal and spiritual life.

Symbolism and Ritual

Symbols of the Ìyáàmi are often avian, such as the ọpá osoronga (staff of the night), which is both a symbol of their power and a ritual implement. Shrines to the Ìyáàmi are generally modest, hidden, or even entirely absent, reflecting the invisible and omnipresent nature of their influence. Offerings to the Ìyáàmi (such as kola nut, water, or palm oil) are given with extreme humility, care, and respect, and the rituals are typically conducted only by those with the necessary authority.

Their presence is invoked for protection, fertility, communal harmony, and, when necessary, for correction and justice. They are also invoked in rites of passage and moments of significant change.

Contemporary Perspectives

In modern Yoruba communities—both in West Africa and in the diaspora—the Ìyáàmi continue to command deep respect, though misunderstandings persist. In the Americas, some syncretic religions (e.g., Candomblé, Santería, Lucumí) have tried to interpret the Ìyáàmi within their own theological frameworks, but the mysteries of the Ìyáàmi remain among the most carefully protected and least understood aspects of Yoruba religion.

Scholars such as Jacob K. Olupona (2014), Wande Abimbola (1976), and Teresa N. Washington (2014) have explored their significance as agents of cosmic order, female authority, and the limits of religious power.

Conclusion

The Ìyáàmi Ṣoròngá embody the profound and sometimes paradoxical truth of Yoruba thought: that the deepest spiritual power is both hidden and ever-present, nurturing and corrective, mysterious and essential. They remind us that true authority arises not just from visible rituals or titles, but from the invisible labor, wisdom, and aṣẹ of the mothers who sustain creation itself.